Pop quiz, hotshot. Name the war being discussed in the following quotation:

Pop quiz, hotshot. Name the war being discussed in the following quotation:"The war, which we can neither win, lose, nor drop, is evidence of an instability of ideas. A floating series of judgments, our policy of nervous conciliation, which is extremely disturbing."

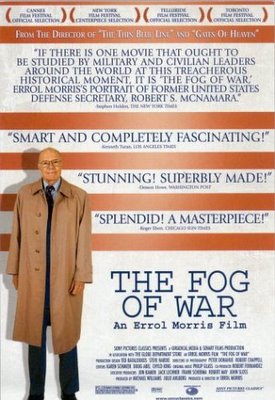

Yeah, I know, you want to say "Iraq," but in fact the war in question was Vietnam. This is a quotation from Senator Hugh D. Scott, Jr. (R-Pa), as quoted by President Lyndon Johnson in Errol Morris' Academy-award winning documentary, The Fog of War. Several weeks ago, this movie appeared on one of the local TV channels, where I was able to watch most of it. Fascinated by the movie, I happened to find recently a VCD copy of the film for sale for a little less than S$5 (about US$3) and, of course, I immediately bought it. The movie is an interview/video memoir of Robert S. McNamara, the highly controversial Secretary of Defense during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations (and, later, president of the World Bank). The movie has the subtitle, "Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara," and these lessons are interesting in their own right. (Although, in an interview, Morris said that McNamara himself didn't like the "lessons" and wanted them deleted from the film.) The lessons are:

1. Empathize with your enemy.

2. Rationality will not save us.

3. There's something beyond one's self.

4. Maximize efficiency.

5. Proportionality should be a guideline in war.

6. Get the data.

7. Belief and seeing are both often wrong.

8. Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning.

9. In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil.

10. Never say never.

11. You can't change human nature.

I'm not going to discuss these lessons at length or try to give the context in which McNamara relates these lessons. For that you should either watch the movie or read the transcript. However, I would like to talk a little bit about Lesson #9, "In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil." When I first saw this movie, I recoiled a bit from this "lesson." After all, we are all taught that "two wrongs don't make a right." And yet, after watching the film last night, I remembered the following ayah from the Qur'an:

I'm not going to discuss these lessons at length or try to give the context in which McNamara relates these lessons. For that you should either watch the movie or read the transcript. However, I would like to talk a little bit about Lesson #9, "In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil." When I first saw this movie, I recoiled a bit from this "lesson." After all, we are all taught that "two wrongs don't make a right." And yet, after watching the film last night, I remembered the following ayah from the Qur'an:"Fighting is ordained for you, even though it be hateful to you; but it may well be that you hate a thing the while it is good for you, and it may well be that you love a thing the while it is bad for you: and God knows, whereas you do not know." (2:216)

And it occurred to me that perhaps McNamara's lesson and this ayah are trying to express the same truth. I know this ayah has disturbed a lot of Christians (especially American Christians) who believe that it gives Muslims a carte blanche to engage in violence*; however, like Islam, Christianity has its own Just War Theory, the roots of which go back at least to the time of the writing of the Book of Judges (see Chapter 5, The Song of Deborah). The problem, of course (regardless of the Muslim or Christian perspective), is in knowing whether one's fighting is properly sanctioned. Is this violence that I'm doing acceptable to Allah (swt), or am I going to pay for it on the Day of Judgment? It is always best in these situations to err on the side of caution.

- Unfortunately, these same Christians are unaware that the Qur'an also places strong limitations on when and how the fighting will be done, along with who (and what) may be engaged in fighting.

For other links, see also:

The Fog of War (Official Site)

The Fog of War (IMDB)

No comments:

Post a Comment